Planting for Climate Change

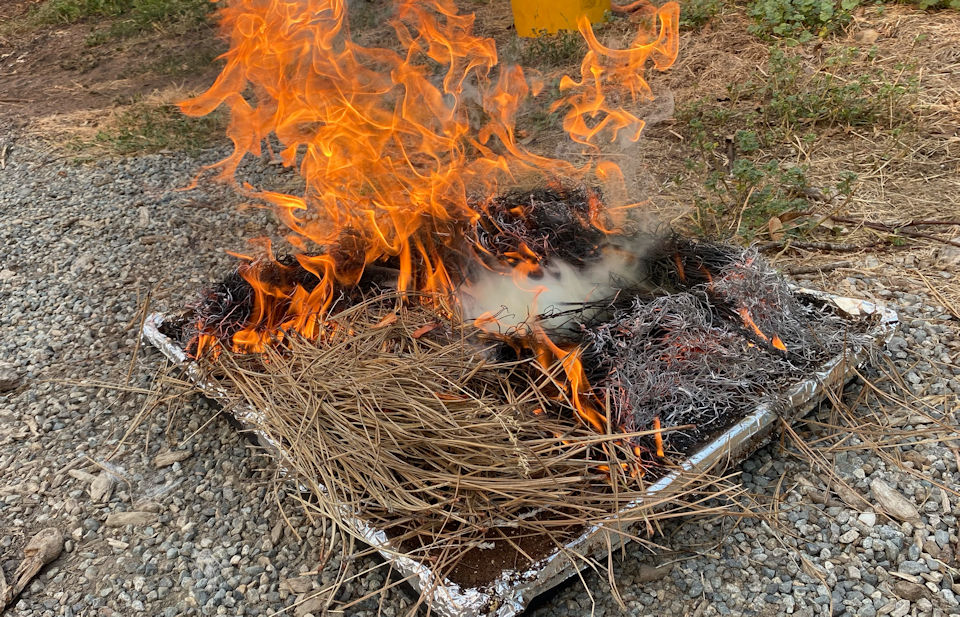

Young lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta var. latifolia) five years post-fire

Our climate is changing at an unprecedented rate, with far-reaching impacts in our region. Winters will be warmer and wetter, with less snow pack created, and summers will be hotter and drier, with lower streamflows. The incidence of extreme weather events will increase, leading to more intense storms, more flooding, more severe droughts and more wildfires.

The native habitats in our environment are essentially moving, to both higher elevations and higher latitudes. How quickly climate and habitats change depends on the rate of increase in greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. With current trends, a recent study in British Columbia indicates that the limits for forest trees are advancing northward at least sixty miles per decade. Some of our native flora and fauna may not be able to relocate fast enough to find a suitable place to live.

How can the planting of native plants be adjusted for this scenario of change? Is it possible to plant for today’s environment AND the environment 30, 50 or 100 years in the future?

The key approach is to select plants grown from seed collected in the area in which they will be planted. These plants have evolved for growth under conditions that have historically occurred there. That the plants are grown from seed, and not cuttings, is the key. Seed-grown plants, especially when the seed is collected from a large number of varied individual plants, contain a far greater genetic diversity than plants produced vegetatively. This genetic diversity can allow some of their number, and their descendants, to have the characteristics needed to survive in the changed future conditions.

It may also be prudent to collect seed from plants found in the lower and drier range of a particular species. For example, in Central Washington Ponderosa pine and Douglas fir can be found growing at elevations close to 1000′ where annual precipitation is below 20″, as well as much higher in the mountains where precipitation is more than double that amount. Biasing towards the more drought and heat adapted selections could provide for better long-term success.

Seedlings of Ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa)

Assisted migration has entered the discussion, in this case, transplanting native plants to a location outside that species’, or variety’s, current range in anticipation that they will be better adapted to the developing climate in the new region. Examples would be planting incense cedar from the central Oregon Cascades to the southern Cascades of Washington, or introducing Garry oak and greenleaf manzanita from Klickitat County into the Okanogan. There is considerable risk with this approach, as there is greater uncertainty with climate models the farther into they future they predict. Some new climates further north may be wetter at critical stages of plant growth while others are drier, for example.

Above all, we need to aim for resilience in our plantings and restoration projects, planting and encouraging both diversity in species and diversity in genetics.

Useful information on how climate change will affect our state is found on the web site of the Climate Impacts Group at the University of Washington

https://cig.uw.edu/about/what-we-do/

Fog filling the Upper Wenatchee Valley in winter